by Robert Romano

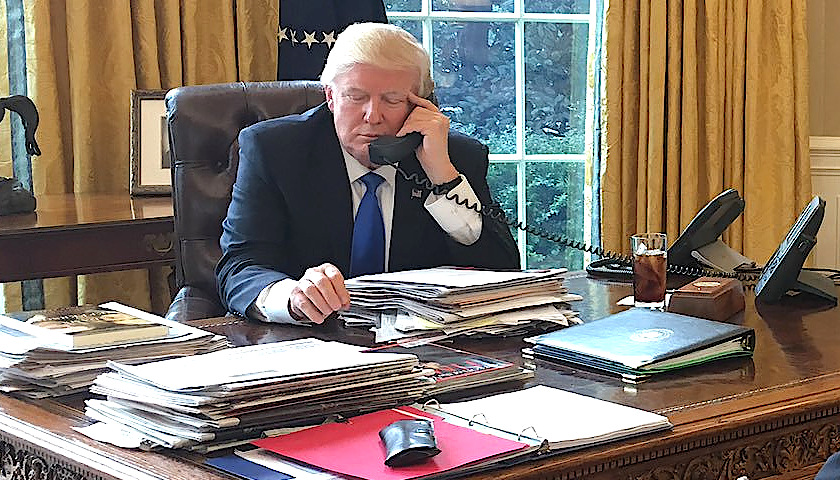

On Oct. 6, the Office of the White House Press Secretary released a statement that after a telephone conversation by President Donald Trump with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan that “Turkey will soon be moving forward with its long-planned operation into Northern Syria. The United States Armed Forces will not support or be involved in the operation, and United States forces, having defeated the ISIS territorial ‘Caliphate,’ will no longer be in the immediate area.”

This is not the first time Turkey has crossed the borders of Syria and Iraq to deal with Kurdish Workers’ Party (PKK) forces — officially designated by the U.S. State Department as a terrorist organization since 1997 — and this undoubtedly won’t be the last as the conflict there escalates.

Turkey’s conflict against the Kurds in Syria and Iraq has been ongoing since 2015, with multiple battles and strikes along the borders with thousands dead. Each time, when the Turkish forces engage in hostilities with PKK and allied groups in those areas, they have not generally been met with a response by the U.S. or NATO beyond public statements. In 2015, the U.S. actually requested Turkey step up its military efforts on the border to deal with fleeing Islamic State forces at the time.

The current operation by the Turks does mark an escalation, but it is also nothing new.

Within a week, Turkey has moved ahead with its invasion of Syria and fired nearby U.S. positions in Syria, highlighting the danger. The U.S. has since announced that almost all forces are completely withdrawing from that country.

On Oct. 14, Trump asked on Twitter very pointedly, “Do people really think we should go to war with NATO Member Turkey?”

That is actually a great question, and underscores President Trump’s relatively cautious approach to the Syrian conflict. Turkey has been a part of NATO since 1952.

When Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974, the U.S. arguably faced a far worse situation because it was two NATO allies, Greece and Turkey, in a conflict and even then the U.S. sided with Turkey. By comparison, this situation doesn’t come close.

Legally, whose side are we on? The NATO treaty says Turkey. We don’t have any treaty with the Kurds — their assistance in the Iraq war and later against Islamic State notwithstanding — and we certainly don’t have one to defend Syria from invasion by Turkey or anybody else. Nor does the U.S. officially recognize the independence of Kurdistan.

Now none of that absolves Turkey from its responsibilities under the United Nations Charter including obligations to maintain international peace and stability and to not invade other countries. But we’d have a hard argument to make, since Article I declarations of war and authorizations to use military force have not been used since 2001 and 2002, when authorizations to go to war in Afghanistan and Iraq were adopted.

Since then, the U.S. has routinely engaged in military operations in countries like Syria, Libya and elsewhere without any debate by Congress. Americans for Limited Government supported members of Congress who rejected Syrian intervention when Obama wanted to go in without Congressional authorization in 2013, and made the same argument when the troops went in to fight Islamic State (the position was vote so they have support) in 2014 and again after Trump took over in 2017 and escalated the U.S. presence.

Even today there is no Congressional military authorization to be in Syria at all and it doesn’t sound like the President wants one as he proceeds with his preannounced plan to pull forces out of there.

Which, on that count, it’s about time. Those forces in Syria never had the full support of the American people’s representatives in Congress. If we’re supposed to be in Syria to fight Turkey, a NATO ally, for Kurdish independence, that should be debated — after the President goes to Congress and requests authorization to do that.

In the meantime, there are other approaches, including sanctions and diplomacy, for which there is authorization, which can be utilized to solve the crisis on the borders there that have been ongoing since 2015. Removing the troops in harm’s way seems the least of it.

Turkey said they were going in and Trump was left to either leave U.S. troops in harm’s way or to deconflict and move them out of the way. He opted for the latter and has since threatened sanctions if Turkey does not limit its operations.

Think of how many wars we’ve been asked to get involved with in Syria the past few years. First, official Washington, D.C. wanted to overthrow Bashir Assad, a Russian ally. Next, it instead decided to kill Islamic State who was fighting Assad, thereby helping Syria. Now, the hawks want to somehow stop Turkey, a NATO ally, in Syria for aiming at a group we have labeled a terrorist organization, who have now sided with Assad and Syria.

You would think Trump had pulled out of NATO or something to hear some members of Congress. Instead he was deconflicting with a NATO ally. It’s a complete mess. Those calling for all these wars cannot even think a few minutes down the road of what the consequences might be.

That’s the state of play. Now that the President and Congress dialing up the sanctions, it is probably a good time to think of the long term consequences. Going forward, the most pressing question is how to keep NATO intact and resolve this crisis? And if it comes to losing all our bases and support in Turkey, what are the costs?

It may come down to removing Turkey from NATO, a very drastic step, but that should not be decided in the deserts of Syria with something awful happening with our troops in harm’s way, it requires deliberation among the allies and Congress.

Article 13 of NATO is clear. Any NATO country is free to leave if they want. Those bases, strategically located where they are, have historically been critical to keeping military parity against Russia but perhaps being located in Turkey is not as important as it once was. On the other hand, the Incirlik Air Base still appears to be a major part of our forward nuclear forces.

The obvious downside of pushing this issue too much with Turkey, including with the sanctions the President is readying, is losing Turkey from NATO forever. In 1974, when Congress did its arms embargo in response to Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus, Turkey months later retaliated by reducing U.S. military conduct in its country to simply NATO activities until 1978 when the embargo was lifted. So it would be wise for President Trump — and Congress for that matter which seems to want to go to war every two minutes but never vote to do so — to weigh all of the costs. This is a provocative move by Turkey, but it is not unprecedented.

– – –

Robert Romano is the Vice President of Public Policy at Americans for Limited Government.